By: DSIRE Insight Team

The NC Clean Energy Technology Center (NCCETC) has been working with the Solar-Plus for Electric Cooperatives (SPECs) project, part of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Solar Energy Innovation Network, to help develop resources to assist rural electric cooperatives to procure energy storage. The SPECs project period is ending later in Spring 2021, and the project team is preparing to publish resources. These include an economic modeling software package, procurement process guidance documents, and a white paper reviewing policy and institutional factors that affect storage deployment at cooperatives. DSIRE Insight team member David Sarkisian has led the SPECs research for the policy review, and identified several state and local policy factors relevant to energy storage at electric cooperatives, which are discussed below. Please check the NCCETC and SPECs project websites later this spring to see the full white paper and other resources.

As energy storage has become a more significant factor in the U.S. electric system, policy at all levels has started to adjust in order to take account of energy storage’s unique characteristics. Because of their unique institutional status, and in some cases, their isolation from larger electricity markets, rural electric cooperatives often appear insulated from policy changes that affect other utilities. However, many types of policy do affect cooperatives, whether through direct requirements and incentives or through indirect effects on other electricity market institutions and the broader electric system.

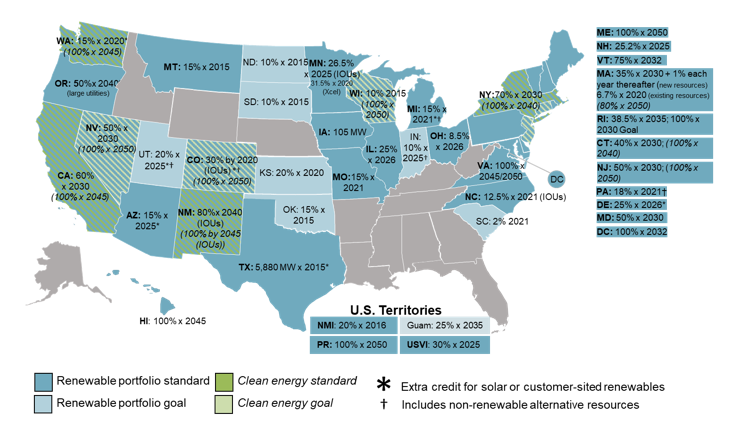

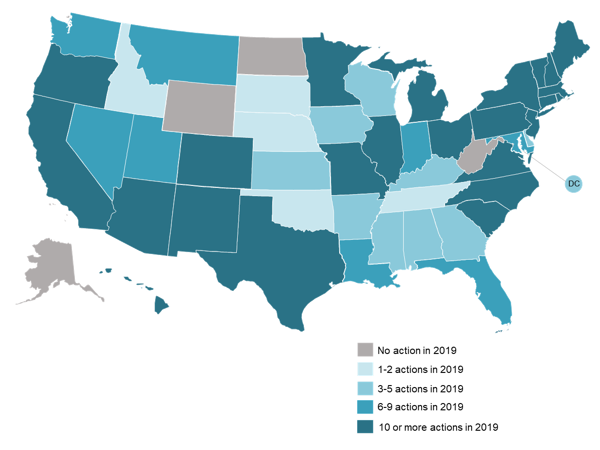

Deployment Requirements

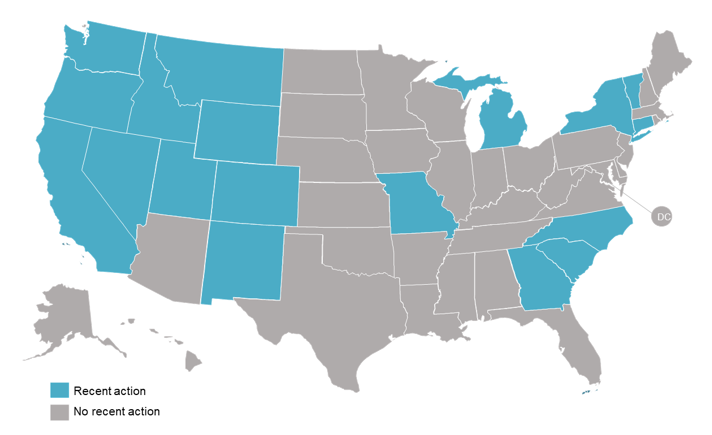

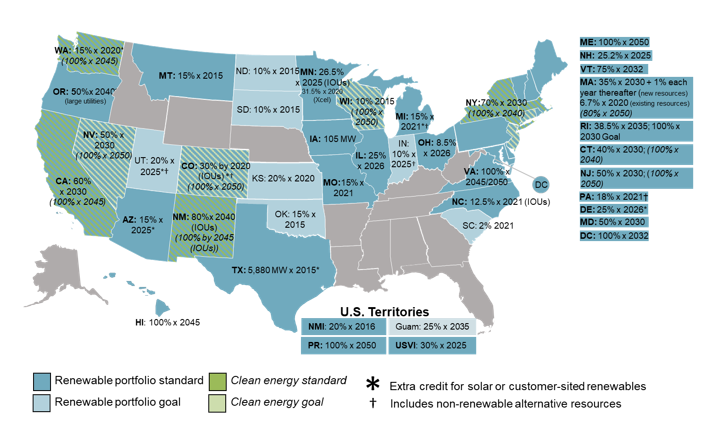

Many states have requirements for utility deployment of renewable energy resources; typically, those requirements have come in the form of a Renewable Portfolio Standard, or RPS.[1] The application of RPS policies to electric cooperatives is often different than for investor-owned utilities. Some state renewable portfolio standards require deployment actions from cooperative utilities, which can lead to exceptions in wholesale contract all-requirements provisions. Additionally, as energy storage is not, in itself, a renewable generation resource, RPS policies’ interaction with storage deployment can differ between states. Some states have adopted policies targeting deployment of energy storage specifically.[2] As with RPS policies, the requirements imposed by these policies may be different for cooperatives than for other utilities; for instance, one state with aggressive storage deployment targets, New York, does not apply them to its cooperative utilities, which are relatively small and few in number.

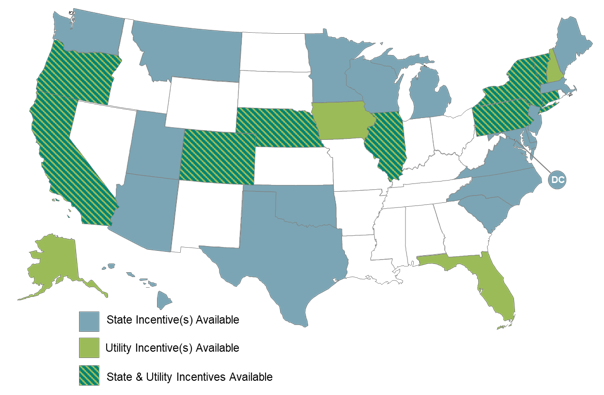

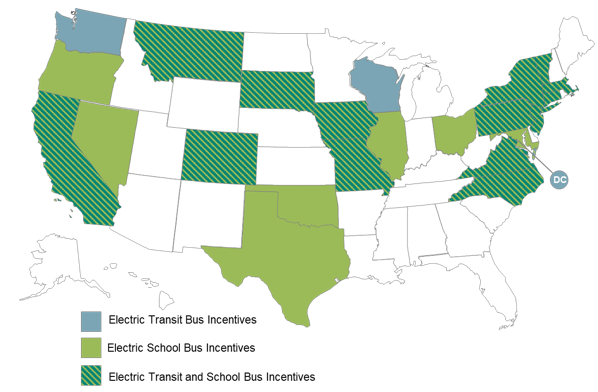

Incentives

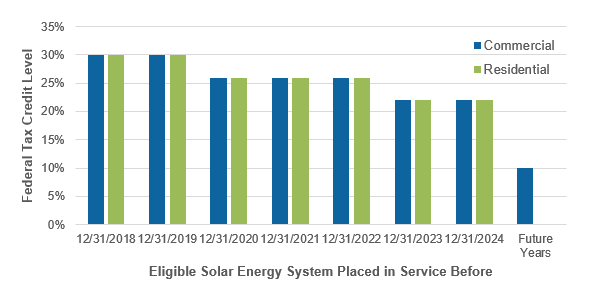

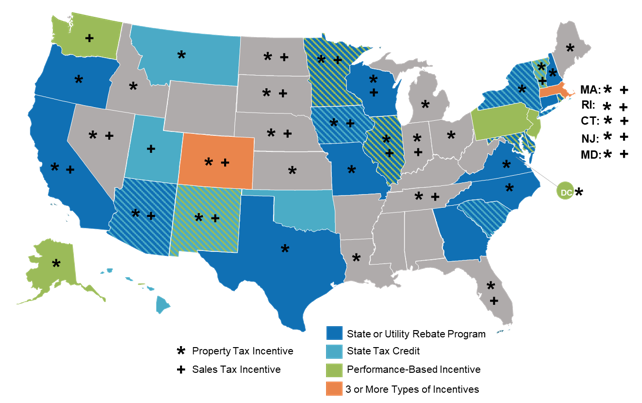

States have adopted tax credits, exemptions, and other incentives for deployment of energy storage. Some of these incentives are not directly applicable to electric cooperatives due to their non-profit status, although organizational arrangements exist that can allow cooperatives to indirectly benefit from income tax incentives. Other incentive programs have been designed to flow through large, typically investor-owned utilities, limiting their applicability to electric cooperatives.

Clean Peak Policies

A few states have adopted or considered “clean peak” policies, which aim to increase the amount of renewable energy being used to meet demand during peak times. As many renewable energy sources are not able to be dispatched on demand without storage support, energy storage plays an important role in complying with clean peak standards. Clean peak policies are similar to RPS policies in that they require a certain percentage of electricity to come from renewable or carbon-free sources, except that for clean peak policies this pertains specifically to electricity consumed during peak times.

The only state that has so far adopted a clean peak standard is Massachusetts, which adopted the policy in March 2020. Arizona and California have also considered clean peak standards. Compliance with Massachusetts’ clean peak policy requires that utilities purchase a certain percentage of their electricity from resources designated as clean peak resources; as the designation of these resources is done by state regulators, utilities do not have to manage their own peaking resources to comply with the policy. Massachusetts does not have electric cooperatives, and does not apply the Clean Peak Standard policy to municipal utilities.

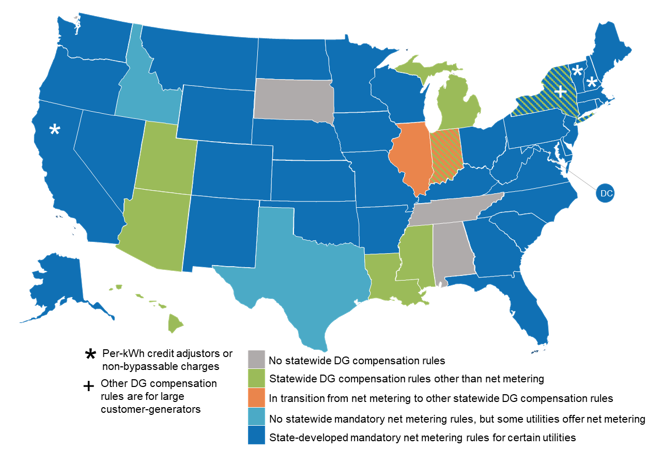

Utility Compensation Policies

State policies for utility compensation of energy storage and other distributed resources pertain mostly to projects installed by customers of electric cooperatives rather than projects installed by cooperatives themselves. However, these policies can potentially affect utility programs that involve customer-owned storage.

Compensation policies here refers to policies like net metering and Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) contract rules that govern how utilities must pay for electricity supplied by customers or other alternative suppliers. State net metering policies do not always apply to electric cooperatives, or may be different for cooperatives than for investor-owned utilities. States that have considered the issue have generally ruled that paired solar and storage facilities are eligible for net metering, although some states, like Hawaii and New York have introduced separate policies for compensation of paired systems in order to manage storage’s ability to draw electricity from the grid.

Resource Planning

Some states require utilities to undertake a process called Integrated Resource Planning (IRP) in order to allow for regulatory commission review of utilities’ longer-term plans for electricity supply. In states that require IRP, the rules do not always apply to cooperative utilities; some states also require utilities to create resource plans, but do not require regulatory approval of these plans. IRPs may also be required for customers of power marketing administrations; customers of the Western Area Power Administration, for example, are required to submit IRPs every five years. Even in areas where cooperatives are required to submit IRPs, these requirements may be more stringent for Generation & Transmission (G&T) utilities than for distribution utilities, as many distribution utilities have few generation assets. This does not mean that distribution cooperatives that meet IRP requirements through their G&T provider should ignore IRP policies; the requirements that IRP policies place on G&T utilities may have significant implications for G&T interactions with their distribution partners. Some state regulatory commissions have required utilities undergoing the IRP process to more thoroughly consider storage as well as other resources available at the distribution level.

Distribution System Planning

As an analogue to generation resource planning processes, some states have begun to implement requirements for long-term planning of the distribution system. As most rural electric cooperatives operate on the distribution scale, distribution system planning may apply to them more directly than does integrated resource planning. As with other types of policy, though, distribution system planning requirements may be different for cooperatives than for other utilities. Energy storage’s capability to be used at both the generation and transmission system and as a distribution system-level resource means that storage can be incorporated into distribution system plans as well as integrated resource plans.

Local Permitting and Zoning

Electric cooperatives are often located in rural areas and therefore might be thought to face fewer obstacles regarding local land use than other utilities and storage developers in more densely populated areas. However, land use issues can still be an important consideration for cooperatives in considering storage deployment, particularly when paired with solar or other generation resources that use a relatively large amount of land.

Paired solar and storage facilities may need to undergo permitting processes at both the state and local levels, although facilities below a certain size can be exempted from some elements of the permitting process. For instance, Virginia has a less strict permitting process for solar facilities below 5 MW in capacity. However, local permitting processes still apply, and local residents with concerns about impacts on agricultural land use or amenity value may present obstacles for these projects. Electric cooperatives are often uniquely situated to create programs that share benefits with local stakeholders, which may let them ameliorate local opposition to solar and storage development.

[1] Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE). (2020, September). Renewable and Clean Energy Standards. North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center. https://ncsolarcen-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/RPS-CES-Sept2020.pdf

[2] Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE). (2020, April). Energy Storage Targets. North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center. https://ncsolarcen-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/DSIRE_Storage_Targets_April2020.pdf